Cramming for No Reason // CAUGHT BY THE TIDES

On the futility of year-end catch-up and the great new film by Jia Zhangke.

It's December and you haven't bought presents for your friends, family, or significant other, because you're too busy watching Conclave. Your Letterboxd mutuals’ scores for the film average out to a whopping 2.5 stars and you loathed Edward Berger's last piece of Oscar bait, but it's the end of the year, and diligence is due. “I gotta catch up on that one.” After Conclave, you'll queue up the latest from Mike Leigh. Of course, you haven't seen Naked, Secrets and Lies, or Topsy-Turvy, and you might as well have walked out on Peterloo given your sleepy indifference to the film at a 9am festival screening. Finally, you'll get around to that festival darling by a first-time director that you'll definitely appreciate but probably won't love. Which one? It doesn’t matter, there's a dozen of these every year.

Why do you do this to yourself? Because you are a cinephile, and a deeply sick person. You can't publish your year-end list – a highly anticipated event for about six people – without giving proper consideration to each and every candidate. The films end up bleeding into one another, and five years from now, you won't remember a single thing about the highly acclaimed 3-star drama that you almost put on your list just to appease the list-judging community. Your efforts to be fully caught up are futile. Unless you are a salaried film critic or unemployed, work will inevitably get in the way of your quest. And even if you are able to dedicate the 31 final days of the year to checking off boxes and making sure your list qualifies in the eyes of the all-seeing commentariat, what kind of cinephile would you be to completely ignore the history of the medium for an entire month in favor of the trends of today? To what will you even compare these films? The canon is always evolving, and nothing exists in a vacuum for the other 11 months of the year, so why are you trying to lay down the law come holiday season? Because you are a cinephile, and a deeply sick person.

I'll stop talking to myself in the 2nd person now, a distancing effect meant to make self-criticism easier on its subject. I've held these thoughts for years now, but I am always sucked back into the world of year-end catch-up come December. Just a few days ago, my annual watchlist looked more daunting than ever. Between struggles with my family and the mental drain of my low-wage dead-end job, I knew I had to be more selective this year. I started deleting films from the list, and I felt free. I'm not going to watch Conclave, Gladiator II, or The People's Joker before making my list. I know what I like, and there is a hard 3-star ceiling on each of those titles. I kept trimming down the list until it only showed promising titles by proven filmmakers. If a rookie outing looks truly good enough for best-of-the-year consideration, maybe I'll see it later, on its own terms, and not sandwiched between two new Hong Sang-soo films. After my cathartic editing, the item of highest priority on the emaciated list was the newest from Jia Zhangke.

Caught by the Tides repurposes footage shot around Jia Zhangke’s productions post-Platform into his most abstract work, which manages to never lose sight of his investigation into China’s changing landscape in the 21st century. Spanning multiple decades, camera formats, and aspect ratios, it roughly takes the shape of a documentary about the life of a filmmaker who never appears on screen or in voice-over, and his muse.

Jia doesn’t sulk in the failures of the past for too long, but he is historically minded as ever, and must show us the last twenty years before taking a look at the present moment and what the future can bring. Early in the film, in the academy ratio, consumer-grade footage that appears to be BTS from the production of Unknown Pleasures, we see an empty, run down “Workers Cultural Hall” with an old portrait of Chairman Mao on display. The painting is so faded that in the master shot, the hat on his head looks more like a boyish bowl haircut, suggesting a warped collective memory. The Unknown Pleasures-era footage, much like that film, is heavy on loud music and the visual distortion that nightclub lighting causes on consumer-grade video.

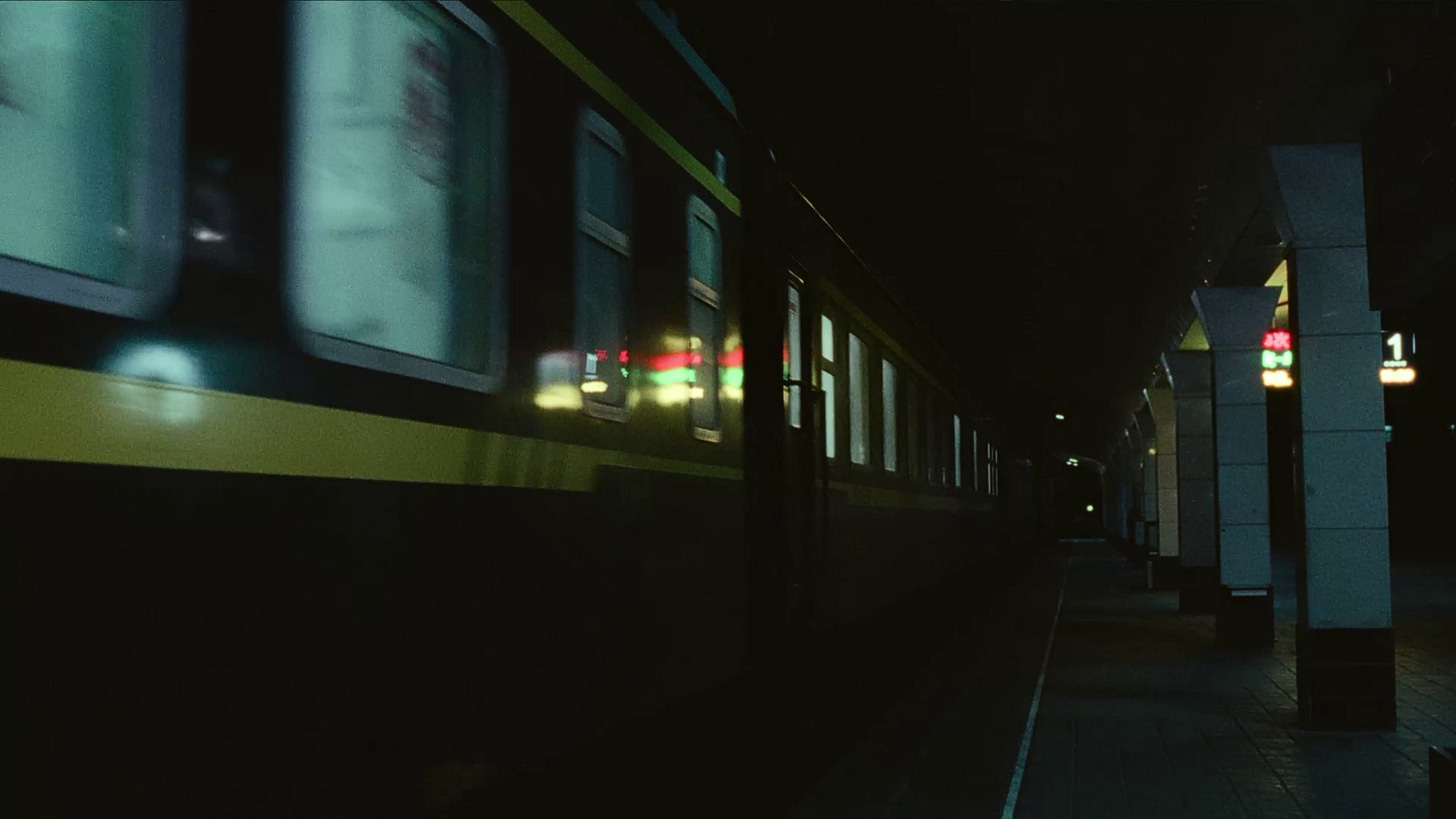

The slightly higher-quality footage set around the Three Gorges Dam is from the production of Still Life, and the segment of the film in which the viewer can begin to piece together the abstracted narrative after the disorienting first segment. We see Zhao Tao beginning her search for ex-lover Bin while the landscape changes in front of our eyes, as it did in Still Life. At one point, Jia cuts from the end of a scene to an image of a train pulling away from the station. This train serves zero narrative purpose; the shot exists only to be superimposed upon by an extreme long shot of Zhao walking away from a decrepit tenement. This is the film’s great example of the abstract extremes with which Jia is working. The extremely loose narrative cobbled together from old footage with a bit of new stuff shot during COVID allows for the filmmaker to work in purely symbolic modes, even more than in his previous films.

After the failed lover’s reunion – where dialogue is replaced with silent-style inter-titles – the film transports Zhao and the viewer to 2022, to a scope frame in glorious 4K. The world is now bordering on antiseptic (thanks, COVID), and Bin’s search for work leads him to an absurd scenario involving a famous TikToker dancing to a Genghis Khan tribute song. This section of the film also sees yet another stylistic evolution for Jia, who takes advantage of new 360 degree cameras to whip and zoom all over the place in two different scenes, jolting the viewer out of what otherwise appears to be a contemporary cinema-of-quality image. After another failed reunion between the film’s two lovers, Zhao solemnly cries while eating a dumpling in her work locker room, a shot that recalled Paul Walter Hauser as the title role in Richard Jewell crying into his donut. To both of these characters, the modern world is unfair.

Zhao Tao’s Qiao Qiao does not speak in the film, she only texts. Contemporary life’s stranglehold on communication is the key to the film, recalling the great works of Antonioni. We are surrounded by monuments of human progress, and yet human connection somehow continues to become more and more difficult. In the final encounter between Bin and Qiao Qiao, she cuts the reunion short to join her running group, to continue the obligatory march of human progress and personal distance.