It’s a hundred degrees in the valley today, and it’s not going to stop. I moved back to Northridge a week ago, and I’ve had the “Extreme UV” warning on my phone every day since. I’ve referenced “the valley” upwards of a hundred times since starting this blog, and I fear that my readers from outside SoCal, or god-forbid outside the US, don’t have the proper context. Resting between two mountain ranges that protect its citizens from the bacchanalia of Hollywood and the fascism of Simi Valley is the San Fernando Valley. Like Los Angeles at large, the semi-suburban sprawl is split into 34 (!) distinct neighborhoods, and the dividing lines of income and ethnicity are as blatant as anywhere else in America. That’s not to say that a majority of the valley isn't the American ideal of a cultural melting pot, but the designated zones for TV writers and gardeners build a clear enough race-class divide to problematize my utopia. The heat is the defining element of the region. The valley, particularly during the summer, is consistently 10-15 degrees warmer than the East Hollywood/Los Feliz/Silverlake region I just moved from, and 20-25 degrees warmer than the coastal delights of the west side. My phone gives me overheating warnings when I sit in traffic too long. I buy a zero sugar lemon-lime Gatorade every day, because no matter how much water I drink, I find myself dehydrated. And it’s not going to stop.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia is a film with which I have a troubled history.

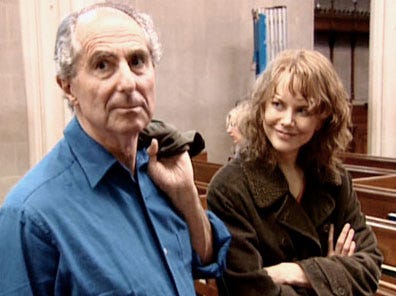

As a cinephile gaining sentience, I mainlined this film. Its grandiose ambitions, bravura camera direction, and local flair (its action takes place in North Hollywood, Studio City, and Reseda) spoke to me at an emotionally confused age, to the point where I realized that cinema was my only option moving forward. I rewatched it eight times over the course of a year, which is really psycho when you consider that this was an era when I did not believe in “casually” watching movies. In an effort to extend my film studies into my personal life, at this point in time, I would turn my phone off and black out my windows with blankets every single time I watched a movie. Melora Walters’ sheets over the windows were natural to me, not the nervous behavior of a cokehead trapped in her own trauma by her dying father.

As I got older, I softened on the film, and grew to prefer the mature works of Paul Thomas Anderson. As I approached (and passed) the age at which Anderson wrote the script, I realized that nobody in their 20s knows nearly enough about the human experience to write a sweeping melodrama like this, where most of the characters are decades older than its author. There’s a lack of life experience, and Magnolia was his first film that deeply relied on bringing lived experience to set. Hard Eight was a Sundance Labs Project (don’t get me started), and Boogie Nights was an exercise in pastiche (albeit a masterful exercise), but this was a true human melodrama about American adult society at the end of the 90s, a decade in which Anderson only existed as a Wellesian wunderkind. The word I kept returning to, in order to describe why I was becoming increasingly put off toward the film’s melodrama, is “overheated”. Julianne Moore’s “don’t call me lady!” theatrics, the doubling down on Philip Baker Hall’s impending death with his incestous molestation, William H. Macy’s ghastly embarrassment at the bar where his young brace-faced crush collects tips from an old wizard; the list goes on. It’s not unlike when I’m driving on the 405 in midday traffic, and the podcast I’m listening to cuts out because my phone is trying to save itself from heatstroke. There’s something in the air, but it’s not just a place, it’s also a time.

The pre-9/11 American Cinema is often discussed in reference to Fukuyama's The End of History. I’m gonna go ahead and blame my good friend Will Sloan for that, because I heard him bring this up with regards to American Beauty about eight years ago, and have heard the reference every month since. This dead end of culture, where capital has defeated collectivism, and America has stomped out the evil spectre of communism, is defined by existential suburban problems that can only exist in a comfortable life. Think about Fight Club and Election in addition to Mendes’ creepy, flippant piece of shit and Anderson’s messy tome. However, on my most recent rewatch of Magnolia, I was reminded of another piece of late 90s art (although published in the year 2000), Philip Roth’s The Human Stain, where culture is defined by the president’s penis. After the Clinton scandal, sanctimony and salacious melodrama became the norm. I’ll quote the master’s exposition here:

No, if you haven’t lived through 1998, you don’t know what sanctimony is… It was the summer in America when the nausea returned, when the joking didn’t stop, when the speculation and the theorizing and the hyperbole didn't stop, when the moral obligation to explain to one’s children about adult life was abrogated in favor of maintaining in them every illusion about adult life, when the smallness of people was simply crushing, when some kind of demon had been unleashed in the nation, and on both sides, people wondered “Why are we so crazy?,” when men and women alike, upon awakening in the morning, discovered that during the night, in a state of sleep that transported them beyond envy or loathing, they had dreamed of the brazenness of Bill Clinton. … It was the summer when — for the billionth time — the jumble, the mayhem, the mess proved itself more subtle than this one’s ideology and that one’s morality. It was the summer when a president’s penis was on everyone’s mind, and life, in all its shameless impurity, once again confounded America.

First, I must take a breath. Roth’s mature prose in this period of his career is beyond exquisite, it flows in a way that evokes his intellectualism and dark humor that I have only seen in James and Faulkner. Second, if this isn’t the perfect setup for the sensibility of Magnolia, I don’t know what is. “Why are we so crazy”? When Melora Walters (who plays the estranged, traumatized, coke-addicted daughter of a quiz show host) tells John C. Reilly (an incel cop, who asked her out after responding to a disturbance at her apartment) that she wants to cut through all the piss and shit, and Reilly can only respond by being taken aback by her foul language, and once again, “the mess prove(s) itself more subtle than this one’s ideology and that one’s morality”. I feel that Anderson is attempting to tap more into Roth’s view of America (despite the fact that The Human Stain is released after this film) as an overheated center of cultural melodrama than Fukuyama’s cultural definitions that stem from geopolitics. However, his sensibility is nowhere near as mature as the great author’s at that point in his career. Luckily, his collaborators like Jon Brion, Robert Elswitt, and the returning ensemble of actors from Boogie Nights can use their experience to elevate the young savant to a position where he can direct a film so indebted to the trials of a life lived.

The film opens and closes on a question of fate and coincidence. Could every incident in the film simply be one of those things that happens? Or is there a grander design?

Anderson provides no answer for this. Instead, he looks at American society, and he sees sickness. He sees loneliness, abuse, addiction, and the disposability of media figures. He sees pathetic people, broken people, and immoral people. He also sees pure goodness in people, like Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Nurse Phil, the most generously-written role of Anderson’s filmography, a true angel who is given a diegetic round of applause after a powerhouse scene with Jason Robards, through one of my favorite audio leads in the history of motion picture editing.

The film was inspired by and structured around the songs of Aimee Mann, whose adult contemporary milieu also suggests an attempt to appear more mature by the auteur. However, it is in the show-stopping musical number, “Wise Up”, that his overheated youth and melodramatic tendencies take over. A singalong that breaks the reality of the film at its emotional low point should just be a non-starter, right? Getting Robards to sing along on his death bed feels like elder abuse every time. I go back and forth on this scene whenever I watch the film. This time, it was as simple as Aimee Mann’s vocal refrain. “It’s not going to stop”. The Valley will continue to live in the shadow of the film and television industries. People will continue to be lonely, and they’ll decide to bravely, even embarrassingly take action, or remain alone. Cycles of abuse will continue in silence until someone makes a radical change. Addiction, lust, cheap thrills, traffic, cellphones, family trauma, and weather are going to define life. And it’s not going to stop.

The film’s flaws run as deep as any person’s, and while I greatly prefer five or six of Anderson’s later works, this one will always mean the most to me. As a resident of the valley, and as an American, whose youth was shaped by the culture of the late 90s.