Privatizing the Public Domain

Mixed thoughts from a concerned cinephile

Vintage Violence is a reader-supported blog about film, literature, and more. I post twice weekly, and a majority of those posts are free. Before I get into this short piece about my mixed feelings regarding the public domain, I would like to make a major announcement about the future of Vintage Violence…

THE VINTAGE VIOLENCE QUARTERLY

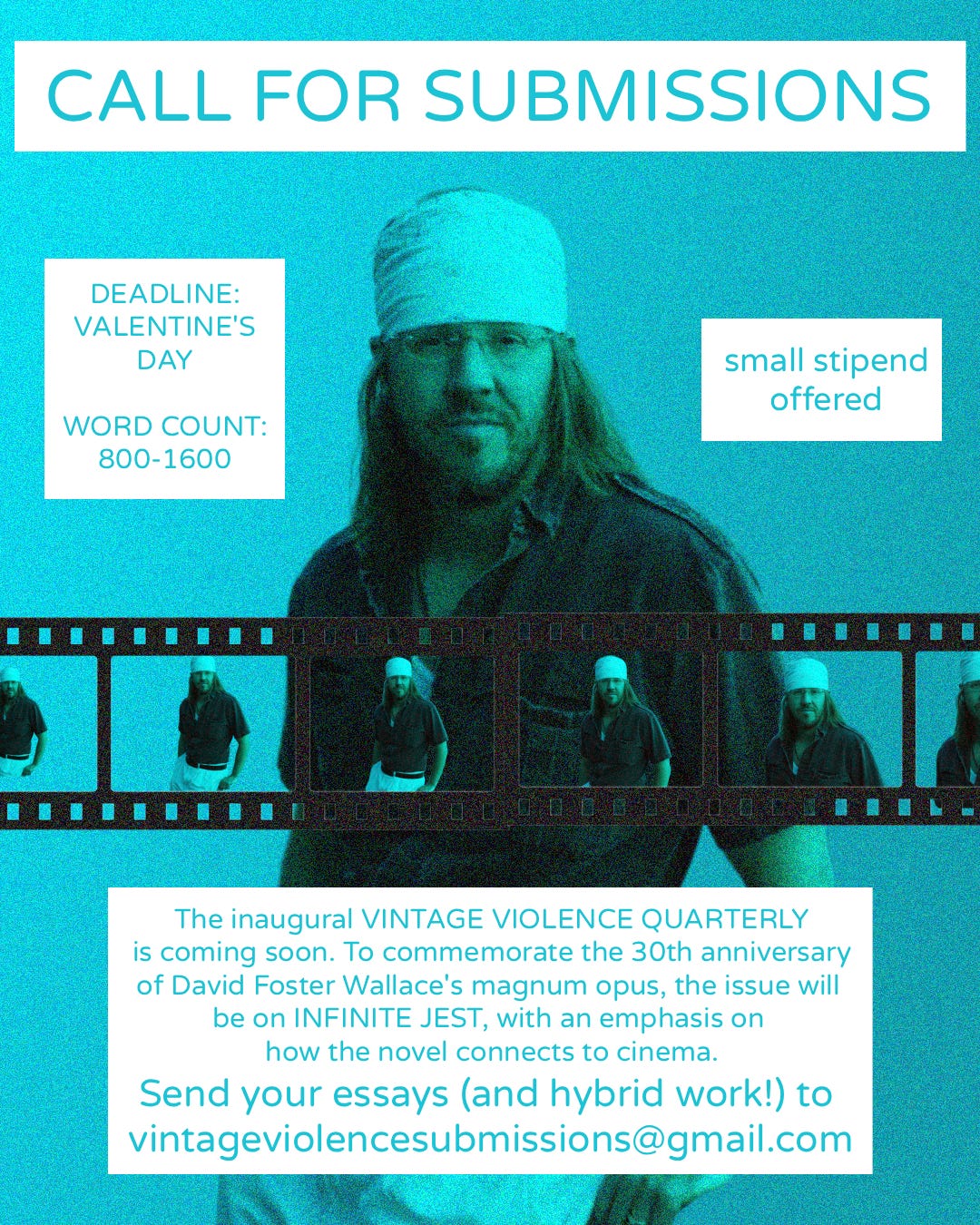

At the end of March, the inaugural Vintage Violence Quarterly will be released. This periodic e-zine, with a potential for limited print runs, will consist of a few original pieces of writing by yours truly in addition to work by some of my favorite critics on a common theme. For the first issue, I’m looking for essays, hybrid work, art, and anything else related to Infinite Jest and Cinema. The deadline is February 14, and I am offering a (very small) stipend that comes directly from a percentage of paid subscription fees. The more paid subs, the higher the stipend.

Send your work to vintageviolencesubmissions@gmail.com.

Privatizing the Public Domain

At the start of every year, copyright experts (and pretenders alike) make a big to-do about the works of art that are set to enter the public domain. Generally, this is something of a communal celebration, that a classic title has been freed from the shackles of its corporate ownership, and now can freely belong to the people. A trend within this yearly ritual always makes me think twice about the system, however. Generally, the free use of these classic films, novels, cartoon characters, songs, etc, is first disseminated through online parody. “Hey, I can make Mickey Mouse smoke a bong or suck a dick, and Disney can’t do anything about it!” Very cool. Next, however, comes the more concrete concern, that of capital.

Public domain repackagers have stocked the home-video bargain bins on an infinite markup since the earliest VHS days, and they’re not going to stop. Now, they also stock the lineups of free streaming channels that come pre-installed on your Roku, to be interrupted by commercials for boner pill subscription services. While companies like Criterion and Kino Lorber will surely acquire the assets for plenty of public titles in order to give them definitive restorations, many will slip through the cracks. Perhaps an enterprising young man will resell As I Lay Dying, this year’s literary public domain headliner, under the name William Fuckner, and make five thousand dollars in ironic Etsy purchases. That same William Fuckner can go on to produce a film based on the classic novel without having to pay a dime in rights, unlike when James Franco produced his adaptation.

However, it should be noted that these aforementioned enterprising young men and women can also, potentially, have the right intentions. Take, for example, Gold Ninja Video , founded by Justin Decloux and Will Sloan. They’ve scanned public domain titles (a 16mm print in the case of White Zombie) and consistently loaded them up with fun and enriching bonus features in an era where studio releases are more and more barebones. Hell, even the almighty Criterion has been slipping when it comes to supplements as of late, and so those indie distributors like Gold Ninja Video are taking advantage of public domain the right way.

I, too, am guilty within this dynamic of art and capital. Now that public domain has reached 1930, the talkie era of cinema, I contemplated putting together and selling some home-produced Blu-rays with supplements of my own editorial selection. It was telling, however, that within five minutes of listing off potential titles, I was doing the math regarding margins on materials, shipping, time, labor, etc. I am impure, as I am predisposed to capitalistic thought. I gave up on the idea nearly as soon as it came into my head. When it comes to creative endeavors that rely on cinephiles giving me their money, I think the podcast and the blog are more than enough, for now.

This is all to say that the public domain system is imperfect. It’s a contradictory minefield for anticapitalists. It’s also the reason that I can host a public screening of Josef von Sternberg’s Morocco without having to pay anybody. I can also play the entirety of standards like “Davenport Blues” on my podcast without getting copyright notices from Spotify and YouTube. These are very clearly good things.

The most depressing potentiality regarding the public domain branches off of a pair of phrases that have been used far too often in film discussions over the last decade. One is a phrase I swore I’d never use again on this blog, but will have to in order to elucidate (or even hint at) the potential catastrophic implications.

It’s free Intellectual Property to be integrated into AI-generated content.

Why would Franco have to pay but Fuckner wouldn’t?